Or, at Least, Knowing Better Doesn’t Make You Persuasive

By Steve Sampson

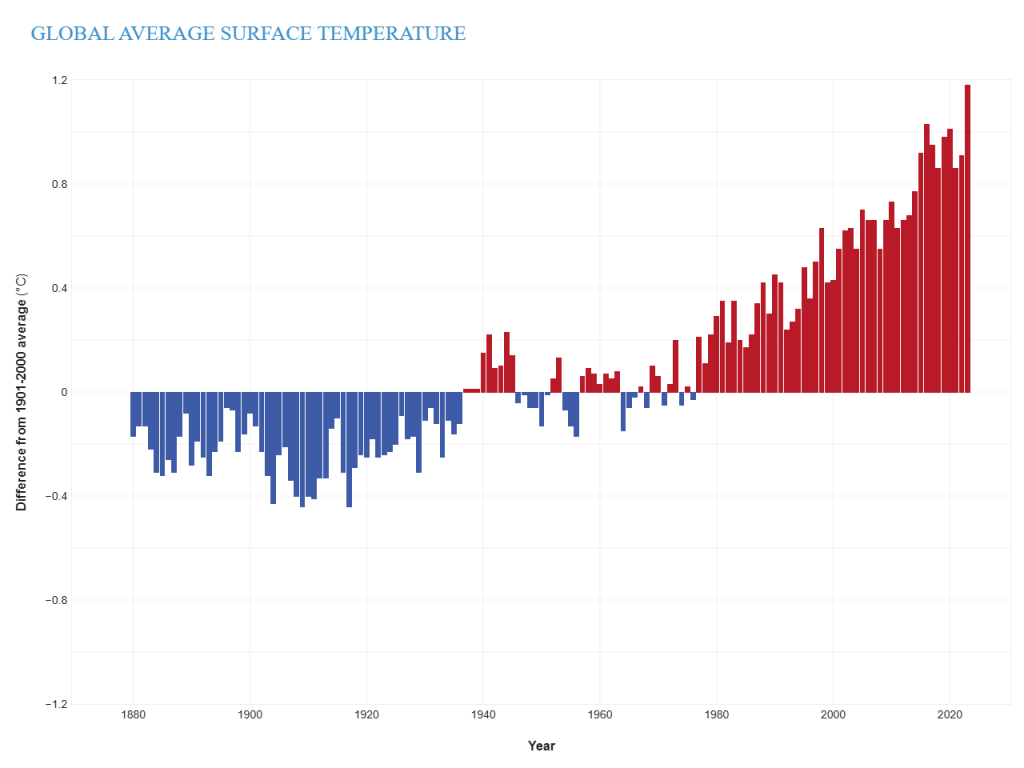

Twenty years ago, I wrote my first piece covering the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—and learned a hard truth about the limits of data in the face of human psychology.

At the time, I was co-editing Knowledge News, a publication designed to help readers make sense of the news cycle by providing historical, scientific, and cultural context. We didn’t report the news; we reported what you needed to know to understand the news.

My goal in this case was to provide a basic guide to the science behind climate change, based on the latest annual report from the IPCC. The logic was simple: climate science is complex, interdisciplinary, and built on the work of thousands of scientists worldwide. The IPCC already had a mechanism for distilling that work into an annual summary—admittedly dense, but widely respected.

These weren’t the words of radical activists or ideological zealots. These were the careful, measured conclusions of climate scientists and policy experts. Safe fare for an audience seeking knowledge.

Or so I thought.

When we published the piece, I was inundated with emails—not with substantive critiques of the science, but with accusations. I was either a dupe or a willing accomplice in a worldwide deception.

The hostility wasn’t aimed at the data itself. It was aimed at who had compiled the data. The scientists. The bureaucrats. The institutions. The shared premise behind the emails was simple: I think these people are corrupt, so I can dismiss what they say outright.

I had assumed my job was to summarize the facts so readers could understand them. I had underestimated how many people had already decided that inconvenient facts were simply optional.

The rhetorical lesson was simple: Data don’t stand on their own. People are more than willing to dismiss data they don’t like—especially if doing so helps them feel smart, independent, and maybe even a little smug.

Data Alone Don’t Drive Anything

In his blockbuster bestseller Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI, Yuval Noah Harari compares two types of people: storytellers and bureaucrats.

- Storytellers use narratives to create shared beliefs, myths, and ideologies. They bring people together through a common sense of identity and meaning.

- Bureaucrats collect, categorize, and report information. They don’t narrativize, they document.

People who believe in data-driven decision-making rely on “bureaucrats” in Harari’s sense. They assume that the people who collect and parse the data do so responsibly—and that the numerical guidance such people produce is (thus) a fast track to the truth.

In the real world, though, the data don’t stand on their own, and what they say often doesn’t prevail. Why not?

As Harari notes, the people making big decisions often aren’t scientists or data experts. They’re storytellers. Or they’re leaders who employ storytellers. Either way, they know how to make inconvenient data seem irrelevant, suspect, or entirely dismissible—including by attacking the people who compiled or analyzed it.

That’s why, in practice, you rarely win arguments with facts alone. You have to begin to win people over before the facts you have to share will even be entertained.

You’ve probably heard the saying: People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care. I’d go further: If people think you don’t like or respect them, they will actively look for ways to undercut you.

Scientists, bureaucrats, and experts often fail to grasp this. They assume that clarity, rigor, and evidence are enough. They neglect the centrality of trust, or they refuse to imagine that people might not trust them.

“But I know better!” they insist. And it doesn’t occur to them how little that means to people who don’t already believe it.

In the end, the data are only as compelling as the people who present them. Other things being equal, people with better data are more compelling than others. But “other things” are never equal, are they?

Exercises to Help You Win Hearts and Minds (Not Just Arguments)

If you want be persuasive, you need the right stories, the right storytellers, and the best data. Here are three exercises to help you think differently about how to find all three.

1. Spot the Storytelling

Pick a recent political or social debate where leaders frequently use stories to dispute or distract from data (e.g., climate change, public health, economic policy, military spending).

Identify one side that relies mostly on storytelling and framing to advance their arguments.

Ask yourself:

- What makes their stories compelling to their listeners?

- How much of it is the stories themselves?

- How much of it is what they believe about the storyteller(s)?

- What stories could you tell that would counter those stories and move listeners toward the facts?

- Who would need to tell your stories to make them most compelling to those listeners?

2. Argue Without Your Data

Think of an argument where you normally rely on data to prove your point.

Now, try to make the same argument without using any numbers or studies. Instead, rely only on stories, metaphors, and emotional framing.

Afterward, consider how you might layer your data back in. Then reflect:

- Is your overall argument better?

- Would it make you more persuasive with people who don’t already agree with you?

3. Make an Expert More Compelling

Think of an expert or authority in your field (or a field you care about) who you think others should follow.

Ask yourself: How could this person be more compelling?

- Are they too technical?

- Do they lack warmth or emotional appeal?

- Do they fail to tell compelling stories?

Rewrite one of their key arguments to make it more engaging and relatable.

Bonus points: Try sharing your rewritten version with someone. Do they find your telling compelling?

Final Thought

Knowing better doesn’t make you persuasive. If you want your knowledge to matter, you have to meet people where they are—using stories and storytellers they can connect with. You also need to grapple with why that might not be you.

In the end, the real contest isn’t between bureaucrats with data and storytellers with anecdotes. It’s between those who seek to tell the truth—by any means available—and those who don’t.

Steve Sampson has more than 20 years of experience as a communications executive, content creator, editor, writer, and team builder. As founder and chief wordsmith at Better Word Partners, his mission is to help other mission-focused leaders find better words, stories, and arguments to achieve their goals.

Leave a comment